The Thomas Steane Louch Memoirs

The TS Louch Memoirs are an important part of the narrative of the 1914-1918 war, particularly for Western Australians.

The custodian of the Thomas Steane Louch Memoirs Mr. Peter Davies, nephew of Thomas Louch, has very kindly donated the Louch memoirs to The Western Australian Genealogical Society (WAGS) so that this important document is made available to the public. We are publishing the TS Louch Memoirs here as part of the WAGS 11th Battalion Project.

923 Thomas Steane LOUCH (M.C. E.D. Q.C.) joined the 11th Battalion as a private, he was given Corporal stripes within days of joining due to his previous experience as an artillery gunner and corporal in the Garrison Artillery.

923 Thomas Steane LOUCH (M.C. E.D. Q.C.) joined the 11th Battalion as a private, he was given Corporal stripes within days of joining due to his previous experience as an artillery gunner and corporal in the Garrison Artillery.

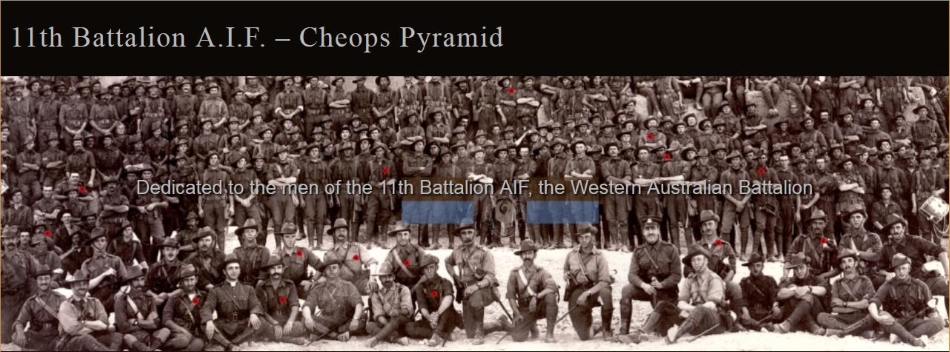

The image at left shows Corporal TS Louch amongst his fellow soldiers of the 11th Battalion on 10 Jan 1915 at the Great Pyramid, he is ID# 625 located in Grid J-16.

He had an exemplary career in the A.I.F.; wounded at Gallipoli while serving with the 11th Battalion, he returned to Australia and then joined the 51st Battalion, was mentioned in despatches three times, received a Military Cross and Bar and the Romanian Chevalier of the Order of the Crown.

He was the first Commanding Officer of the 16th Infantry Battalion in 1936, first Commanding Officer of the 2nd 11th Battalion at the commencement of World War 2, served with the 2/11th in North Africa and Greece and was again mentioned in despatches; serving as Commanding Officer of the 29th Brigade (Queensland) he retired from the army in 1943 with the rank of Brigadier.

Thomas Louch served for some 50 years as Lawyer at the Western Australian Bar, a King’s Councel (later Q.C.) and Honorary Life Member of the Law Society of Western Australia, well liked and respected in the Perth community he was Life Governor of the Princess Margaret Hospital for Children a considerable philanthropist and a Director of The West Australian Newspapers Limited.

Brigadier Louch died in 1979 and his ashes were scattered to the winds at Karrakatta Cemetery in Perth.

Whilst serving in the 1914-1918 war, Thomas Louch wrote many letters home to his family. Many years after the 1939-1945 war he set about recording his memoirs, using many of the letters he sent home as a basis for his personal record of the 1914-1918 conflict. The memoirs were completed in 1970.

Below is the first installment of the T.S. Louch Memoirs.

In The Ranks, 1914-1915 – A Personal Record

Foreword

At the beginning of the war a man in the ranks was told little about what was happening; and in battle he could see only what took place in his immediate vicinity. This, then, is merely an uncritical narrative of what I actually did and saw while an N.C.O. in the 11th bn A.I.F. From the Australian Official History I have taken several quotations referring to myself, and I have used that work to check dates etc. But I have relied for the most part on my memory, supported by letters written at the time. The draft was put on tapes for the benefit of Dick Clarke, who was blinded in the war, and considered bt him and “old Tom” Rose, the only other survivor of my section; and I am indebted to them for their comments.

T. S. Louch

Perth

Anzac Day, 1970.

Synopsis

Chapter 1 1914 – Blackboy Hill – 11th Bn – Voyage to Egypt

Chapter 2 1915 – Mena Camp – Training in Egypt – Lemnos

Chapter 3 Anzac – wounded – Hospital in Cairo – return to Australia.

Chapter 1

In l914 I was serving my articles as a Law Clerk in Albany, Western Australia, having recently returned from school in England, 0n 5th August I was called up for service with the Garrison Artillery; but as soon as recruiting opened I enlisted in the A.l.F. and on Sunday, 16th August, in company with 25 other recruits from Albany I left on the night train for Perth. We were given a tumultuous send-off by half the town: but the warmth of our farewell gave place to a cold night in this train. We had no blankets, and there was no room to stretch out in the crowded second class carriages: so we spent most of the time regailing ourselves with scones and meat pies at the various refreshment rooms enroute. As it turned out this was just as well. There was no one in charge of our party, and our only orders were to detrain at Bellevue and make our way to Blackboy Hill camp.

Blackboy Hill

Having alighted at Bellevue at 8 am., we asked the solitary porter how to get to Blackboy Hill, but he said that he had never heard of it. Some time later the Stationmaster arrived, and he was no wiser. However, he rang the Military Headquarters in Perth and was told that if we went back along the railway line for about a mile we would come to some high ground on the right, and that was the site of the camp. We followed these instructions but found only virgin bush, and we were just about to move on and look elsewhere when Captain McLennan, the Quartermaster, arrived on the scene with several G.S. wagons with tents. Having ascertained that we were recruits from Albany he ordered us to get busy and unload the wagons, which we did. While we were doing this he made a rapid survey of the campsite, and put in pegs to indicate where the company lines were to be. He then told us to start pitching the tents. We asked about something to eat: but he said we should have had breakfast before coming into camp. So we spent the morning pitching tents and marquees. Major (Drake ) Brockman arrived about midday, and we tackled him on the subject of food. But he said that there was a war on, and that we couldn’t expect much the first day; there would be a meal later on, and meanwhile we must go on getting the camp ready. When we had pitched all except the last row of tents it started to rain, so we knocked off and took shelter.

In the late afternoon organised bodies of men from Perth, Fremantle and the Goldfields began to arrive, and they were accommodated in the dry tents we had erected. Subsequently Captain Reilly informed us that with other men from Bunbury we were to form ‘H’ Company and that we had better start to erect tents for ourselves. This we did, but the ground was soaking wet. When it was dark we got a meal of stew and tea, and were issued with blankets and ground sheets. So ended our first day in the A.l.F. We did not complain; all we wanted was to get to the war before it was over. The Governor, Sir Harry Barron, a distinguished General, had stated publicly that it could not possibly last for more than four months.

In the late afternoon organised bodies of men from Perth, Fremantle and the Goldfields began to arrive, and they were accommodated in the dry tents we had erected. Subsequently Captain Reilly informed us that with other men from Bunbury we were to form ‘H’ Company and that we had better start to erect tents for ourselves. This we did, but the ground was soaking wet. When it was dark we got a meal of stew and tea, and were issued with blankets and ground sheets. So ended our first day in the A.l.F. We did not complain; all we wanted was to get to the war before it was over. The Governor, Sir Harry Barron, a distinguished General, had stated publicly that it could not possibly last for more than four months.

Our first job next morning was to go out and gather firewood for the cooks, so that they could prepare breakfast. Water had been laid on to the camp, and there was a washing bench with half a dozen taps; but it was days before we got showers or proper latrines. The food was monotonous – stew for every meal, plus half a dozen loaves of bread and two tins of jam per tent per day. The bread and jam were collected each morning from the Q.M’s store in a blanket, and stowed away un-hygenically in the tents until eaten. There were no mess tents, tables or chairs; one ate sitting on the ground. No attempt was made to improve the cuisine because we were told that when we got into the field each man would have to cook for himself. There was no canteen; but in the evenings itinerant pie merchants came to the precincts of the camp and did a roaring trade.

At the start there was a good deal of shuffling about as men were drafted to the 8th Bty on to two companies of the 12th bn that were being raised in W.A. Having been a gunner I thought that perhaps my right place would be in the Artillery; so l went over to see Major Beesell-Browne commanding the 8th Bty, who was some connection of mine by marriage. He asked me what experience I had had with horses, and when I said ‘none’, he summarily rejected me saying that the war would not last long enough for them to teach me to ride. However, on the strength of the two stripes I had had in the Garrison Artillery I was made a Corporal, and put in charge of a section of men from the South-west, of whom more hereafter. I knew little about infantry work, but this did not matter; the only function of a section commander in those days was to see that his men carried out the orders that came from above. He was not expected to shew any initiative.

11th Battalion

The C.O. of the Bn was Lieut Col. Lyon Johnston, a militia officer from Kalgoorlie, commonly known as ‘Tip’ because at the end of any route march he used to say “Well, it’s been a long way to Tipperary, but we‘ve got here at last.” He did not make much impact on us, but rate Adjutant in Capt J.H. Peck, a permanent officer, who ran the battalion in the early stages. The R.M.O. was Capt Brennan. These three officers, and Major Roberts, the second in command, rode horses. Peck looked like a Centaur: the others like sacks of spuds. The ‘H’ company officers were Reilly and Buttle, who trained us efficiently in the elements of infantry work, which to them was a very serious business. We could not help noticing the hilarious proceedings of next door neighbours, ‘G’ company. They were commanded by Capt Croly, who had formerly belonged to some lrish regiment. He had dug up one of his old uniforms and a green cap – all rather suggestive of comic opera. He was always joking, and had remarkable powers of invective. But he had the gift of saying anything without giving offence. The only other officers with whom we came in contact at the time were the subalterns of the day who came along at meal times, blew their whistles, said ‘Any complaints’ and moved on hurriedly in case they should receive any. Most of the orders we got came to us from the R.S.M. through the orderly sergeants. The R.S.M. – W.0. Graves – an impressive figure with a waxed moustache, was an old British Army N.C.O., and to the N.C.0’s at any rate, he ranked next in importance to the Adjutant.

Soon after arrival in Camp we were issued wit slop-made dugarees, of the cheapest description, which fitted where they touched and stained everything blue. In addition each man got a white rag hat, two thick flannel shirts, two pairs of long woollen underpants, an abdominal belt, two pairs of boots, one pair of socks, and a small cake of soap. The soap was not for use as it had to be produced at kit inspections which were held frequently. We were then made to send our civilian clothing home. Everyone was ashamed of the blue dungarees. There was leave on Sundays, but instead of going into town we used to get our girl friends to bring out a picnic lunch. Dick Clarke‘s sisters made all the arrangements, but I think we paid for the chickens. My sister was a protégée of Lady Barron and one day a signal was received at Bn HQ., summoning me to lunch at Government House on the following Sunday. Peck was determined that I should not disgrace the battalion by going in dungarees, so he made one of the officers remove the badges of rank from his tunic and fit me out with the rest of his uniform for the occasion. l told the Governor what had happened and being an old soldier he was amused. It may only have been a coincidence, but shortly afterwards we were issued with the standard A.I.F. uniform of jacket, breeches, puttees and hat. This was an uncomfortable garb for an infantry soldier; but it took two world wars before the authorities realised this and changed to something more suitable.

We spent eleven weeks at Blackboy Hill, and most of the time was devoted to recruit training – squad drill, rifle exercises and musketry. Our only weapons were rifles and bayonets so, compared with the task of the modern, soldier there was little to learn. Battle training was confined to advancing in short rushes and flopping down on the whistle blast. There was nothing leisurely about this: we worked with a stop watch, the time being taken from the whistle to the last man down. After much practice, par for the exercise was about two seconds. By the time we were proficient, we were all suffering from gravel rash. But there were occasional variations. Our leaders took the view that it was impossible for us to embark on a troopship in an orderly manner unless the drill had been well rehearsed beforehand. So every now and then we paraded in full marching order, carrying our kit bags, and proceeded to the Helena Vale racecourse where we went through the pantomime of embarking on the grandstand. And then there was Black Monday. We were ordered to parade in full marching order at midday. The C.O. said that some men had had too much beer at the week-end, and the remedy for that was to march it off. So, without any lunch, we set off and marched non-stop by a devious route to the top of Red Hill, on the Toodyay road. When night fell it was announced that the field kitchens could not get up the hill, so there would be no tea. It drizzled during the night, and next morning, cold wet and hungry, we marched back to camp. After that lesson we always carried chocolate and biscuits in our haversacks.

We spent eleven weeks at Blackboy Hill, and most of the time was devoted to recruit training – squad drill, rifle exercises and musketry. Our only weapons were rifles and bayonets so, compared with the task of the modern, soldier there was little to learn. Battle training was confined to advancing in short rushes and flopping down on the whistle blast. There was nothing leisurely about this: we worked with a stop watch, the time being taken from the whistle to the last man down. After much practice, par for the exercise was about two seconds. By the time we were proficient, we were all suffering from gravel rash. But there were occasional variations. Our leaders took the view that it was impossible for us to embark on a troopship in an orderly manner unless the drill had been well rehearsed beforehand. So every now and then we paraded in full marching order, carrying our kit bags, and proceeded to the Helena Vale racecourse where we went through the pantomime of embarking on the grandstand. And then there was Black Monday. We were ordered to parade in full marching order at midday. The C.O. said that some men had had too much beer at the week-end, and the remedy for that was to march it off. So, without any lunch, we set off and marched non-stop by a devious route to the top of Red Hill, on the Toodyay road. When night fell it was announced that the field kitchens could not get up the hill, so there would be no tea. It drizzled during the night, and next morning, cold wet and hungry, we marched back to camp. After that lesson we always carried chocolate and biscuits in our haversacks.

The main topic of conversation was the date of departure, as to which there were many rumours based largely on the Delphic utterances of the C.O’s batman, We were not told that our sailing was held up because the German warships Gnisenau and Scharnhorst were at large, and possibly in the Indian ocean. But at long last two transports arrived at Fremantle and all leave was cancelled. At this juncture my mother returned from England, and as a special concession Peck gave me three hours leave one evening to see her and say good-bye. We had dinner at the Plaza Hotel and I ordered a bottle of German Sparkling Hock; but so great was her detestation of the Germans that I had difficulty in persuading her to drink any of it.

Voyage to Egypt

On 31st October we boarded the Blue Funnel liner Ascanius. The 10th bn from South Australia having embarked at Adelaide occupier the forward part of the ship and we were accommodated aft.

On 31st October we boarded the Blue Funnel liner Ascanius. The 10th bn from South Australia having embarked at Adelaide occupier the forward part of the ship and we were accommodated aft.

As H company we always marched at the rear of the battalion getting the full benefit of the dust raised by those in front – and there were no black roads in those days – but on this occasion we scored, for by the time the other companies had been allotted to messes below, the troop decks were full, and we were put into one of the deck houses which has been a Smoke Room when the ship carried passengers.

There was little room: but by comparison these were luxurious quarters. As soon as the last man was on board the ship left the wharf and anchored in Gage Roads to wait the sailing of the remainder of the convoy from Albany, where it had assembled.

Two days later we moved to the rendezvous, and our eyes goggles when the armada of 38 transports escorted by the Australian Light Cruisers Melbourne and Sydney, and the Japanese Battle Cruiser Ibuki, came into view. The convoy was in three lines, and we took station third from the front in the left column.

Two days later we moved to the rendezvous, and our eyes goggles when the armada of 38 transports escorted by the Australian Light Cruisers Melbourne and Sydney, and the Japanese Battle Cruiser Ibuki, came into view. The convoy was in three lines, and we took station third from the front in the left column.

Ascanius, like all troopships, had been fitted out by the Navy according to standard specifications to take the maximum number of men in the space available. Down below, in the open cargo decks, tables and forms had been installed for messing, and hooks were provided there for the slinging of hammocks. Water was scarce and severely rationed; and there were no showers. Only the sanitary arrangements were satisfactory, for which we probably had to thank Florence Nightingale who was instrumental in getting reforms after the Crimean War. During the day, except at mealtimes, everyone had to be on deck. There was scarcely room to move, let alone drill or take any exercise. Throughout the voyage it was hot, and the men just sat about playing ‘Housie-housie’ which was permitted, or ‘Crown and Anchor’ which was forbidden. Hammocks were issued and most of the men tried sleeping in them for a night or two; but they were too short for tall men who found the hard deck more comfortable, if they could find a place to spread their blankets. The respect for prescriptive rights was quite remarkable, and one who had by two or three night’s occupation established a claim on a particular bit of deck, rarely had to fight for it afterwards. By day there was usually something to do. We found out the names of all of the ships and the various troops they were carrying; and when we discovered that messages were sent from the flagship by lamp, which seemed to be winking all day, we studied the Morse code with the idea of discovering what was going on. But we never became proficient enough to monitor these messages tapped out by the expert signallers. The nights were long, and there was a total black-out. Having spread out our bedding we sat on it, and discussed nearly every topic under the sun. We also practised our schoolboy French, which we expected to need very soon. In the early days at Blackboy Hill my mates had been the Clarke brothers and Vic. Cargeeg. Later I got to know Charlie Puckle of G Company. He and I had similar tastes, and we became close friends. Through him we got to know several men from the 10th Bn who joined our evening discussion group. Guy Fisher and Jose l remember, but there were others. ln the end we had representatives from nearly all the public schools in Victoria, South Australia and W.A. and four or five from English schools: and there was much amusing and intelligent talk.

The food was more varied than we had had in camp: but there never seemed to be enough of it, and we were always hungry. There was a canteen of sorts to serve the whole ship: but there were nearly 2000 troops on board and anyone wanting to buy a packet of biscuits might have to wait in the queue for hours before being served. This caused dissatisfaction, and it remained for one of our-chaps – ‘Pink Top’ so called because under that trade name he had carried on a greengrocery business in Perth before the war – to find the solution to the problem. For a small commission he undertook to buy anything that was required and went round after breakfast taking money and orders. He then made up a bulk order which he handed in to the canteen and returned later to collect and distribute the goods. He never made a mistake and no one grudged him the commission he earned.

The Standing Orders for Troopships were designed to find employment for as many men as possible, in order to keep them out of mischief; and the first night out from Fremantle we were called upon to supply a guard on the potato store down in the bowels of the ship. It was rough and most people were seasick as well as homesick. As l have never known what it is to be seasick l volunteered for the job, and three men elected to come with me. It was a smelly job, and one by one the members of my guard succumbed to the motion of the ship and the stench of the potatoes; so I sent them up on deck where they could be sick more comfortably, and for the rest of the night l sat and watched the potatoes myself. The Ship’s Orderly officer – a very young subaltern from the 10th bn visited me on his rounds, and was not at all satisfied with this arrangement; but while he was making up his mind whether I should be ‘crimed’ for allowing the guard to absent themselves from duty the stench of the potatoes overcame him too, and beat a very hurried retreat. Afterwards for curiosity I read the Standing Orders and found that they had evidently been drawn up for the Crimean War. There were all sorts of prescribed bugle calls: one I remember was the signal to ‘Avast heaving on the pumps’.

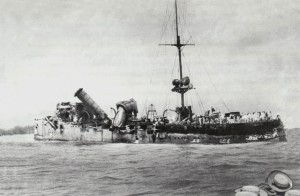

After breakfast on 9th November we saw HMAS Sydney streaking off ahead of the convoy, to be followed by lbuki which passed close by us belching black smoke and clearing her decks for action. Someone thought he could hear gun fire, and then at 11.30 a signal came to say that the Sydney had engaged the German cruiser Emden and put her out of action. Later we heard the story.

After breakfast on 9th November we saw HMAS Sydney streaking off ahead of the convoy, to be followed by lbuki which passed close by us belching black smoke and clearing her decks for action. Someone thought he could hear gun fire, and then at 11.30 a signal came to say that the Sydney had engaged the German cruiser Emden and put her out of action. Later we heard the story.

Unaware of the presence of our convoy the Emden had passed close in front of it during the night, and had landed a party to destroy the cable station at Cocos Island. When they realised what was happening the cable staff sent out an SOS, which was picked up by our naval escort, and the Sydney and lbuki went to the rescue. The Emden was no match for the Sydney which could have stood off out of range of the Emden‘s guns-and sunk her. But in his keenness to finish off the battle before the lbuki could take a hand, Captain Glossop closed with the Emden, and there were some casualties on the Sydney.

Our discussion group approved of his action and considered that it would have been unsporting to sink the Emden without giving her a chance to fire back; but in Australia, Glossop was subjected to some criticism.

The Emden was beached at North Keeling Island, the survivors – many of whom were badly wounded – were picked up by the Sydney and taken to Colombo. The party of German sailors who had landed to destroy the cable station were more fortunate; they stole a lugger and escaped.

The Emden was beached at North Keeling Island, the survivors – many of whom were badly wounded – were picked up by the Sydney and taken to Colombo. The party of German sailors who had landed to destroy the cable station were more fortunate; they stole a lugger and escaped.

The convoy coaled and took on water at Colombo, but there was no shore leave. We were not surprised at that, but were disappointed that no bum-boats came alongside to sell fruit. Ten days later, in the early hours of the morning, Ascanius overtook and rammed Shropshire, the troopship in front of us. The jar and impact woke us up, the alarm bells sounded, Shropshire turned on her lights, and the remainder of the convoy, not knowing what had happened, scattered. After the collision Ascanius drew up alongside Shropshire, and then by suction the two ships were drawn together with the result that her starboard and our port lifeboats, which throughout the voyage had been slung over the side, were smashed to bits.

When the ships disentangled Shropshire steamed away and we hove to until the extent of the damage to our port bow was ascertained. It turned out to be a hole 25′ by 3′ (feet) above the waterline. Meanwhile all on board Ascanius had paraded at emergency stations, prepared to abandon ship if necessary. Our emergency station was on the deck outside our mess. As the lifeboat to which we had been allocated was in bits and pieces we realised that if the worse came to the worst we would still have to take to the water and swim about until we were picked up after dawn. It was a still warm night, and flat calm, so we were not unduly alarmed. We felt as there were so many ships about it would not be long before someone came to the rescue. After discussion we decided that our best course would be to jump over the side naked, except for a rag hat to prevent sunstroke, carrying the cumbersome cork lifebelt in one hand, and in the other a cigarette tin containing money, watch, cigarettes and matches. Having prepared ourselves accordingly we awaited the order to jump. At that stage Major Roberts arrived on the scene bringing with him the ten or twelve hospital nurses who were told to join our party. Some of us near the door of our mess made to go inside to get pyjama pants to cover our nakedness: but Robets drew his pistol, waved it in the air, and said that the first man to panic would be shot. We tried hard not to laugh, but stayed where we were draping the lifebelts round our middles until allowed to stand down.

At first light HMS Hampshire closed with us and the Captain, using a megaphone, said that he wished to compliment the officer of the watch on the clumsiest bit of navigation he had seen in his thirty years at sea. There-upon, as a curious demonstration of one eyed loyalty to the side, he was spontaneously answered with yells of abuse from hundreds of throats on our ship. Having ascertained that we were not in need of immediate assistance Hampshire made off, and we were left to limp into Aden.

At first light HMS Hampshire closed with us and the Captain, using a megaphone, said that he wished to compliment the officer of the watch on the clumsiest bit of navigation he had seen in his thirty years at sea. There-upon, as a curious demonstration of one eyed loyalty to the side, he was spontaneously answered with yells of abuse from hundreds of throats on our ship. Having ascertained that we were not in need of immediate assistance Hampshire made off, and we were left to limp into Aden.

Subsequent, happenings I described in a letter of 6th December:

“We spent a day in Aden coaling; it was very dirty and we were not allowed ashore, so we were not sorry to leave the place, which is a barren desolate spot at best. However, they allowed the boats to come alongside, and we bought Turkish Delight and figs which made a change. All through the tropics we were never once given any fruit, or even lime juice. At times the heat was awful: we used to wear nothing but pyjama pants …. We waited a day at Suez. The Hampshire was anchored about 80 yards away and we saw the Captain of the Emden and the Kaiser’s nephew being taken on board as prisoners. They had come from Colombo on the Orivito … We did not enter the Canal until seven in the evening. Whilst we were going through we had 150 armed men on deck and everyone else below, in case we should be attacked … (When morning came) we found the whole of the canal patrolled by our troops. As we went along we signalled to them and told them who we were, and asked who they were. They were nearly all Indians, though we did see one company of the Egyptian Camel Corps. Nearly all our fellows were wildly excited as very few of them had been out of Western Australia before. We passed an Armoured Train full of Territorials going to Ismailia – a weird looking affair. The engine is in the middle, in front and at the back there are machine guns with just the muzzle sticking out, and all along the coaches there are narrow slits for rifles. There are no widows, and the whole affair is painted khaki.”

Arrival in Egypt

“We arrived at Port Said and tied up to a buoy just opposite the Casino Palace Hotel, a large building on the sea front. We took on water all day: and we are able to buy dates, figs, oranges and Turkish Delight – in fact we nearly all made ourselves sick. At night several chaps swam ashore: they were nearly all caught when they returned, and put in the cells. Certainly after being on board for four weeks it was very tempting to go ashore: and we were less than lO0 yards from the shore. We came onto Alexandria by night, and have been here two days now waiting to disembark. The railway is the trouble: they can only give us ten trains a day.”

We had been expecting to go to England, and the decision to divert the AIF to Egypt was a sudden one taken for two reasons. Canadian soldiers in England were very dissatisfied at the lack of amenities in their camps at Salisbury Plain, and were playing up in the towns; so Sir George Reid, the Australian High Commissioner in England, who was afraid that there would be trouble if the AIF was brought to England in the winter before there were proper camps to receive them, suggested to the War 0ffice that we should complete our training in Egypt.

This suited Kitchener, who was worried about the defence of Egypt. Turkey had come into the war against us, the Khedive had fled to Constantinople, British subjects had been expelled from Jerusalem, the Turks were thought to be planning an attack on the Suez Canal, and the British Government was about to declare a Protectorate and replace the Khedive with a Sultan of their choice. So we went to Egypt to help maintain order if necessary, and to repel any Turkish attack on the canal.

Continued in Part 1, Chapter 2