Hector Miller - RTA - ID# 439

Loyalty and a bitter twist of fate....

Hector Miller's grandson Keith, tells us about his grandfather

"... for a man who endured a host of unfortunate circumstances in life, he was a remarkably kind person and was bereft of the bitterness that seems a common affliction today. Perhaps the hardscrabble life of turn-of-the century Australian immigrants simply didn’t accommodate self-pity and complaining."

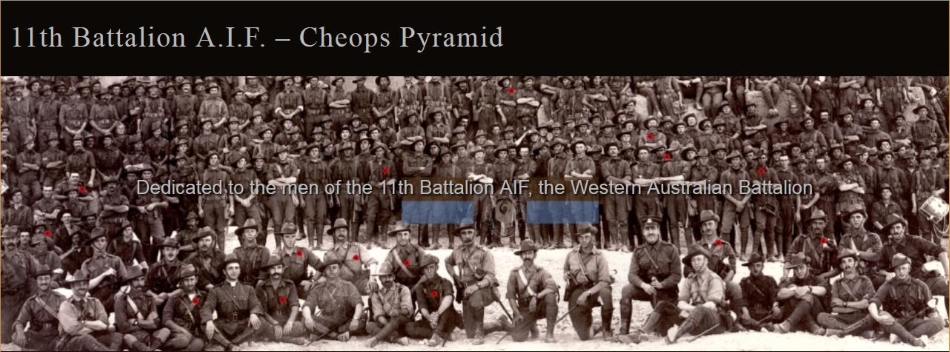

Ser#460 Private Hector Miller

ID#439 Cheops 10 Jan 1915

As his grandson, I never saw an ounce of bitterness in his life and wished at times a bit of his calm acceptance of life’s vicissitudes would rub off on me.

Early days

Hector Miller was born on the last day of October, 1889 near Cossack, in northern Western Australia.

His father William Miller had emigrated from Scotland to Western Australia with his brother Robert. William married Rachael Simpson (nee Chapman), a widow with at least five children of her own, before giving birth to Hector.

[caption id="attachment_4587" align="alignright" width="180"] Cossack 1898[/caption]

When Hector was only two years old his mother Rachel died of cancer.

When Hector was only two years old his mother Rachel died of cancer.

Two years later his father William died of tuberculosis.

Orphaned at age four, Hector was brought back to Scotland by his Uncle Robert and was raised by doting aunts and uncles in Rothesay. Because of their relative wealth and the fact that they were childless, the aunts and uncles lavished attention upon the young Hector and sent him to several of the finest public schools in Rothesay and Glasgow.

At the age of eighteen Hector chose to return to Western Australia and lived with his half-brother David Simpson in the port city of Fremantle. Family oral history suggests that Hector took on a number of skilled and unskilled jobs and was briefly involved in operating a taxi company.

War is declared

At the outbreak of the Great War, Hector enlisted as a Private and was given the Service No. 460 in the 11th Battalion which at that time consisted solely of West Australian recruits.

On his twenty fifth birthday, after months of training at Blackboy Hill on the outskirts of Perth, Hector and the others members of D Coy broke camp, entrained to Fremantle and sailed on the Ascanius, their eventual destination being Alexandria, Egypt.

Further training ensued, both in Egypt and on the Greek island of Lemnos before Hector took part in the ill-fated Gallipoli Campaign.

Gallipoli and after

[caption id="attachment_4584" align="alignleft" width="230"]

Hector aged 18 in Scotland

As a teenager boarding at Aquinas College near Perth in the mid-sixties, I spent many weekends at the Nedlands home of my grandparents, Hector and Kathleen Miller.

My parents were at Exmouth at the Northwest Cape so my grandparents were very welcoming to a homesick grandson. Two of my sisters attended Loreto Convent School and were often at my grandparents’ home on weekends also.

During those weekends I spent many hours talking to Hector about his experiences in WWI.

My memory is that he said his first wound came while he was in a landing boat that was used to ferry soldiers to and from the beachhead at Anzac Cove.

landing boat that was used to ferry soldiers to and from the beachhead at Anzac Cove.

His military record shows he was wounded on April 25, 1915, which was the day of the initial landings at Gallipoli.

He told me that by the time the bullet from a Turkish machine gun hit his thigh it was spent, meaning it had traveled so far that it did not penetrate deeply into his leg. He dug around in the wound with his finger until he could feel the back end of the bullet. With his fingertips and a knife he managed to pull it out of the thigh muscle, and with a certain amount of pluck, decided to keep the bullet by putting it in a tin of Gallaher’s Two Flakes Tobacco.

The bullet and tin remain today with relatives in South Australia.

Wounded, evacuated and separated from his mates

Hector was evacuated from the beachhead several days later and was hospitalized in Alexandria, Egypt, and from there was shipped out to England in July 1915 for further treatment on his leg.

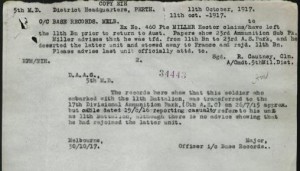

While in England, away from his mates in the 11th Battalion in the Dardanelles, he was transferred to the 301st Army Services Corps, 17th Divisional Ammunition Park, and found himself a member of the British Expeditionary Force in France driving ammunition trucks.

On Nov. 12, 1915 Hector was injured again, this time he broke his forearm and was evacuated to a hospital in England to recuperate. He did not mention this injury to me and it is not clear how it happened, but he told me he did not like driving ammunition trucks and found it dangerous due to the constant shelling behind the lines by the Germans. He was also homesick for his mates in the 11th Battalion who were still suffering through the devastating stalemate at Anzac Cove.

In December 1915 all Anzac forces were withdrawn in a pre-dawn evacuation that caught the Turkish Army off guard. The 11th Battalion was briefly routed through Britain before redeploying to France.

This is the pivotal point where Hector made a fateful decision that was based upon his deep camaraderie and loyalty to his mates, but was not sound military protocol.

Reunited with his battalion

Sometime in January 1916, Hector had recuperated sufficiently from his broken forearm that he was released from the hospital and was expected to rejoin the 301st Army Services Corps as an ammunition truck driver. Instead, wanting desperately to be reunited with his mates in the 11 Battalion, he deserted from the 301st and stowed away on one of the many military vessels plying the English Channel.

Somehow, without official papers and almost certainly with the acquiescence of his unit’s enlisted men and some officers, he was quietly allowed to rejoin the 11th Battalion as an infantryman. He never mentioned it to me, nor did anyone in the family ever retell the story of his desertion.

It is not difficult to imagine why he did it: an orphan and more or less alone in the world since he was not married, the closest thing to a tight family unit were the mates he trained and went to war with. [caption id="attachment_4581" align="alignleft" width="300"]

Hector is in the image left, fourth soldier from the right with his face partially obscured by the light. He sent this photo to his half-brother in Fremantle.

Hector is in the image left, fourth soldier from the right with his face partially obscured by the light. He sent this photo to his half-brother in Fremantle.

The fatefulness of this decision came to a jarring conclusion on July 25th 1916.

On July 1, the Battle of the Somme commenced. It was one of the biggest battles in the history of warfare, with more than 1 million wounded or killed on both sides and lasted until November 1916. Australian Forces were involved in several sub-battles including the Battle of Pozieres.

During that ferocious battle the Germans counter-attacked with a devastating bombardment, including poison gas shells. Hector was hit by a German gas shell and to take an optimistic view, it was just as well that it was not a high-explosive shell or he would certainly have died on the French soil that day. Instead, either a chlorine or phosgene gas shell exploded right beside him, mangling his left leg. My grandfather told me that he knew it was a gas shell because it made a “whistling sound” like a canister tumbling through the air.  He said it exploded near him and ripped into his left leg.

He said it exploded near him and ripped into his left leg.

The wound to his leg was severe and he said he languished in a field hospital for many hours until someone attended to him. When they found out it had been a gas shell, they triaged him immediately. He wore a brace on his left leg for the rest of his life in order to provide support for the calf muscles that had been cut away.

Understandably he never wore shorts and once rolled up his long slacks to show me what was left of his leg. His thigh muscle seemed fine, but atrophied due to lack of use. But below the knee there was literally only skin covering bone. I remember trying to hide my shock.

In handwritten notes that I discovered when I inherited Hector’s 1945 edition of the history of the 11th Battalion, he wrote the following:

Evacuated to Le Harve, called Vieux Belgium, en route – conditioning low worsening – arrived afternoon – repeated requests for attention left leg. On midnight, Dr. said, ‘Why didn’t you tell us of gas?’ Rushed to operation at midnight – Evacuated by hospital ship to England. Long train journey to Bristol Military Hospital (was Bristol Lunatic Asylum). On danger list. Too low to amputate. Had continual hydration treatment. Ossified around stripped shin. Many muscle sinews (very dark colored, like charred cotton). Evacuated to Harefield Hospital, near London.”

Hector’s leg wounds were too severe for continued service and he was sent by ship back to Western Australia where he was discharged on September 1917. He had served in the Army for three years and eighteen days, two years and one hundred and eighty one of those days abroad.

Despite his disability Hector took on a number of demanding jobs after the war including delivering mail in the Northwest as well as hunting crocodiles.

At one point he became blind, perhaps from trachoma, and returned to Fremantle.

Hector married Kathleen Adams and they eventually settled in Nedlands with three children, Ray, Brenda and Hector Junior.

Hector Senior later worked for the Australian Broadcast Corporation transcribing sporting scores from towns throughout the state. He died at the ripe age of seventy nine on 6th Oct, 1968.

For a man who was an orphan and who suffered three injuries in WWI, he was a remarkably affable and kind man. He was proud of his service and doubtless would have not changed a thing, including his desertion to be with his mates in 1916. That single act of loyalty led to his physical crippling, but did nothing to dampen his enthusiasm for life, family and adventure.

Article by Keith Yocum

Our thanks to Keith Yocum for this tribute and the insights into the life of his grandfather, Hector Miller.

Keith Yocum was born in California in the 1950s although his family had brief stints in St. Louis, Missouri and numerous homes in the Canal Zone. His family finally moved to Northern Virginia in 1963. In 1967, his father went to work for the U.S. Navy and was posted to the US Navy submarine communications base on the tip of Northwest Cape, Western Australia. It was then that Keith attended Aquinas College and got to spend weekends with his maternal grandfather, Hector Miller. After returning to the US, Keith obtained a Master’s Degree in Journalism and has worked in that field ever since. A resident of Massachusetts, USA, he is the author of two novels Daniel (2009) and Titus (2013).