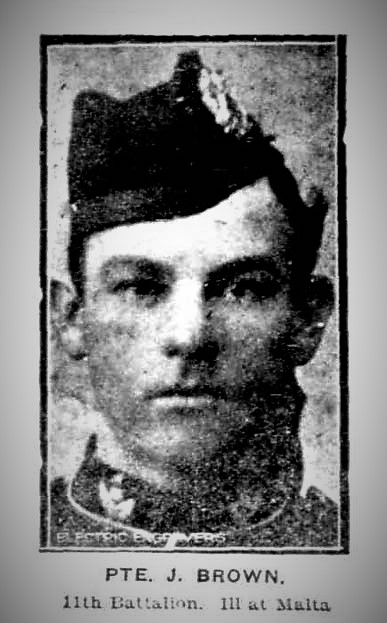

James BROWN, 1042 Private - RTA - ID# 213

Optimism defeated...

It was a typical West Australian summer’s morning and Jim Brown felt the heat intensifying in his room, a tiny front addition to his sister’s modest home in the inner Perth suburb of Leederville.

By 9am, the house had emptied. Everyone gone about their various tasks for the day. Jim locked the door and reached under the bed for the rope he’d secreted. Positioning a chair under the main rafter, he slung the rope over the beam, secured it tightly and fashioned a noose. Without pausing, he placed the loop around his neck, tightened it and kicked the chair away. It was Monday 16th February 1948. Jim was 59.

A Queenslander by birth but a Scot by heritage, James Brown was eleven when he arrived in Western Australia with his grandparents, uncle, parents and siblings in 1899. The men of the family were carpenters and they chose to settle in Leederville, a popular working class suburb on the fringe of the capital city, Perth. The discovery of gold had resulted in a massive increase in the State’s population and the Browns belileved their prospects of steady work were good.

The 20th century began without incident but its second decade was a turbulent one for the family. In 1911, Jim’s grandmother passed away, followed two years by his uncle at the relatively young age of 45 and when war was declared in 1914, Jim, now twenty five, was working as a house painter in the employ of Richard Sasse of Mount Hawthorn. Excerpts from his diary give a picture of a man eager to ‘do his bit’ and see something of the world outside Leederville. At 5’4”, Jim was below the minimum height requirement of the fledgling AIF but his experience of military protocols and discipline as a member of a Fremantle reservist regiment likely swayed the enlisting officer.

Jim’s war diary commences with his initial attempts to enlist in Melbourne:

At the start of the war, I was in Melbourne. When the first volunteers were called for, was in the first dozen to do so at Victoria Barracks, St Kilda Rd

The first military person I met was Sergt-Major Storey and the first question he asked, Open your mouth? Did so! No good, said the SM. I had a couple of bad ‘molars’.

So I straightaways back to West Australia, arriving on the Sunday, and the Monday I volunteered again, & was accepted, providing I had my teeth fixed up & arrived in camp at Blackboy Hill, about 12 noon on the Tuesday, somewhere about 16 Sept 1914.

About camp life I kept no record, but on 31st October 1914 we broke camp to embark on the HMAT Ascanius, after all getting aboard, we pulled out to Gage Roads there to await further orders.

Dad and sisters came out in a launch to see me.

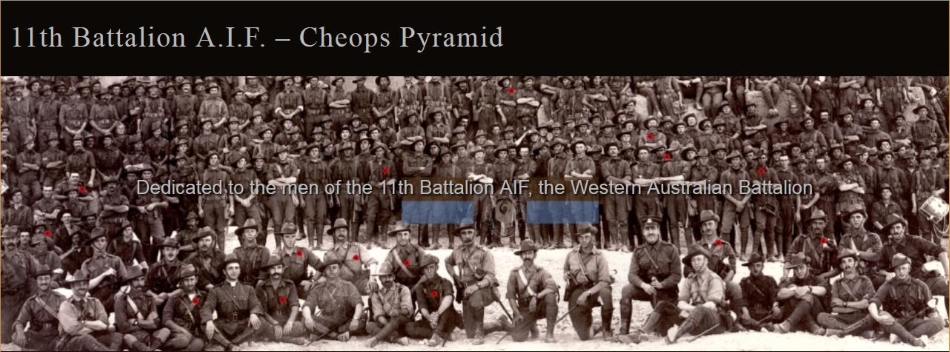

As Service Number 1042 in the famous Western Australian 11th Battalion, one of the first units ashore at the Gallipoli landing, Jim featured in the famous photograph of the 11th Battalion taken on the Great Pyramid of Egypt in January 1915. His is the only explanation as to how another Leederville man, the much loved ‘Pink Top’ (David Simcock), came to occupy the highest position in the photo.

As Service Number 1042 in the famous Western Australian 11th Battalion, one of the first units ashore at the Gallipoli landing, Jim featured in the famous photograph of the 11th Battalion taken on the Great Pyramid of Egypt in January 1915. His is the only explanation as to how another Leederville man, the much loved ‘Pink Top’ (David Simcock), came to occupy the highest position in the photo.

We then lined the Pyramids (sic) to have our photo taken, myself and a few others, we were too high up, and out of focus for the photographers. So down we had to come. “Pink Top” was the highest up now”

Jim’s descriptions of the initial months of his four years and twenty four days of active service are quite unexpected for his observations, the detail he included and the way he expressed his feelings about events and those around him. Jim had a wry, quirky view of the world.

Wed 2nd Dec (1914) – Some boat this, run aground in the Suez. Soon got off though. Arrived at Port Said at midday. All along the banks is nothing else but barb-wire entanglements, & Indians on guard.

There’s something in the seaside air alright, as there was two fights on board. Plenty of warships and troops in Port. Also, plenty of fun, what with ‘bum boats’ and variety artists, a girl with a violin. Some of our chaps climbed the rope down into the briny and swam ashore from there. The water was very cold, as one chap nearly got drowned.

Tues 3rd Dec (1914) – Left the port and anchored outside. Nearly drawn into fisticuffs with a hot headed Scotchman.

“Pink Top’ heaved overboard two cases of oranges because the officers wouldn’t allow him to scramble for the men. Anyway, we retrieved them, and took them down to our mess-tables, where those that were lucky got one. Rumour has it that he made £45 on the trip by buying at the canteen for men who didn’t like waiting in the line, for any length of time. Pink Top would buy at canteen prices, & charge a 6d or 7d extra per item. The men didn’t mind. Received our identification discs. Expect to leave here in a couple of days.

Mon 25th Jan (1915) – Left camp at 8am for rifle range. Done 5 rounds in skirmishing order by Platoons, then five rounds by sections. Made a very poor show and was severely criticised by Major Roberts. This of course made our Lieut a bit cross. He made us come back to camp at a fast ‘bat’ which of course made us all cross. Had a riot or near to one at teatime. Officer of the day was doing his rounds for complaints, instead of doing it the usual way. He stood at the door of the mess-hut and blew a whistle as if we were a lot of slaves. Of course the boys didn’t like this and ‘hurrayed’ him. He done A and our mess- room and then went to C Coy mess-room. The whistle again, and they hurrayed again, only worse than before. The officer done his ‘block’ and called the guard out and arrested one man which of course made the men mad. He, the officer, soon cleared out and all the NCOs were put under open arrest. I daresay we will hear more about it in the morning.

Whether it was simply bad luck or that he’d been born with a poor constitution, Jim spent most of the War years battling ill-health. After months fighting on the Gallipoli Peninsula and over the next four years, he spent long periods of time in Field Hospitals with recurring bouts of influenza, septic sores, scabies, boils, myalgia and mumps and eventually arrived back in Fremantle in November 1918 carrying no ‘visible’ wounds of war.

Whether it was simply bad luck or that he’d been born with a poor constitution, Jim spent most of the War years battling ill-health. After months fighting on the Gallipoli Peninsula and over the next four years, he spent long periods of time in Field Hospitals with recurring bouts of influenza, septic sores, scabies, boils, myalgia and mumps and eventually arrived back in Fremantle in November 1918 carrying no ‘visible’ wounds of war.

1919 was a dark year for the family. Jim’s grandfather Phillip Brown died in March and five months later, Jim’s younger brother Phillip, a hardware shop assistant also passed away. Phillip had enlisted in the AIF in January 1916 and been discharged six months later as medically unfit. Undeterred, he re-enlisted four months later and was sent overseas with the 44th Battalion in December 1916.

Phillip suffered from a severe form of epilepsy and within a year, having spent most of his service being treated in England, he was returned to Australia and discharged for the second time in November 1917.

As the Australian survivors returned home from the Western Front to resume their former lives, Jim, now living with his parents and sisters in his grandfather’s former home, applied for a £200 loan to extend the weatherboard house. He was intending to add two brick rooms and a verandah and indicated that the house would eventually be his. He also indicated he was ‘single (so far!)’.

His application was rather cryptically withdrawn some three months later.

Well dear Sir, I wish to withdraw, anyway for the present, as I cannot see my way clear to carry on, owing to unforeseen happenings occurring, viz, receiving benefits under intending marriage.

As his sisters gradually left the family home to marry and set up their own homes, Jim grew restless and moved to Wubin as a general hand on his brother-in law’s farm at Wubin. He also applied for a small plot of land 11½ miles west of that wheatbelt town and asked for sustenance until his block was surveyed.

With no farming experience or financial resources however, his dream of a productive farm was only that, and within a few years, he was back in Leederville working again as a house painter and applying for assistance to connect sewerage to the house he shared with his parents. Western Australia was starting to feel the effects of the Great Depression.

In the autumn of 1932, his brother-in-law, the bootmaker Walter Vincent was killed one evening in a motor car accident on the corner of Charles and Vincent Streets, Leederville. Jim’s parents died several years later and the family home was sold. Two of his sisters bought houses opposite one another in Mount Hawthorn, presumably with their share of the proceeds of the sale of the family home and Jim, now almost sixty, found himself without a home and family of his own.

Jim's own world had shrunk to the tiny verandah room on the front of his sister’s house and the physical demands of his work were becoming too arduous.

Jim's own world had shrunk to the tiny verandah room on the front of his sister’s house and the physical demands of his work were becoming too arduous.

With his spirit quashed, he chose to end his life on that summer’s day in February 1948. Funeral notices indicated that Jim had found some camaraderie at the RSL and the Druids Lodge and was a supporter his Union.

No doubt Jim hoped his life would include a family of his own and a diary filled with details of heroic deeds and it didn’t turn out that way. His heart was too heavy to go on.

May you now rest in peace James Brown, Ser# 1042.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

Sincere thanks to Vern Harrop for sharing with us, the diary of his great uncle, James Brown.

Thanks also to Marjorie Bly from the Perth Office of the National Archives of Australia for providing swift access to the Repatriation Department files of Jim and Phillip Brown and her ongoing support of the 11th Battalion project.

Researched and written by Julie Martin