Frank Henry Burton ADCOCK (394) - KIA - ID# 343

Frank Henry Burton ADCOCK (394) - KIA - ID# 343

Frederick Brenchley ADCOCK (1044) - KIA - ID# 341

Frederick Brenchley ADCOCK (1044) - KIA - ID# 341

"The War will involve much suffering"

April 25, 1915

As the small craft moved silently towards the beach and dawn broke over the Dardanelles, so began the last day in the lives of brothers, Fred and Frank Adcock.

Their experience of war was short and brutal. A Court of Inquiry held in France twelve months later declared that both men were killed in action on that April day.

Fremantle, Western Australia - April 25, 1915

For their mother Charlotte Adcock, living a world away in a boarding house on the corner of Solomon and South Streets, Fremantle, it was the start of a lifelong battle with the emotional pain of war, a battle she had to wage for a further three decades.

Family Background

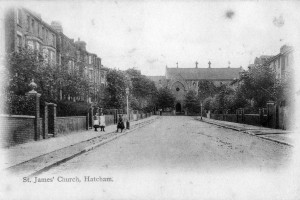

The story of the Adcock boys had its beginnings on a September day in 1887 when the twenty seven year old, Charlotte Maria Atkins married John Adcock in the church of St James in Hatcham, Lewisham, Kent. Charlotte had grown up in the seaside town of Sheerness, Kent, the eldest of the twelve children of Charlotte Brenchley and James Fielder Atkins, a clerk with the Admiralty.

A literate man, he was keen for his children to have an education and by the time she was twenty one, Charlotte had qualified as an Assistant Teacher and was employed in the small Leicestershire town of Syston. It was here that she met John Adcock from nearby Somerby, the second son of the local blacksmith, William Adcock and his wife Ann Burton.

Charlotte and John, an Ironmonger’s Assistant set up home in Melton Mowbray and two years later, Charlotte gave birth to a son, Frank Henry Burton Adcock.

Charlotte and John, an Ironmonger’s Assistant set up home in Melton Mowbray and two years later, Charlotte gave birth to a son, Frank Henry Burton Adcock.

In the summer of 1893, a second son was born and christened Frederick Brenchley Adcock. On the night of Sunday 31 March 1901, a census was conducted throughout England and it recorded Charlotte and the two boys living in Melton Mowbray.

John however, was a lodger in a boarding house in West Leeds, Yorkshire.

Had the family group fractured; had John to go further afield to find work?

Whatever the reason for John’s absence from his home in 1901, it appeared to carry through to his death at Great Malvern, Worcestershire in 1907 at the relatively young age of forty five. His effects, valued at over £1000 were left to his widow Charlotte, his father and an Ironmonger, Samuel Garner. Charlotte and the boys, now eighteen and fourteen were left to fend for themselves.

Australia Bound

Charlotte’s closest sibling was her brother George Usher Atkins, her junior by three years, who had immigrated to New South Wales in 1896. Lured by the prospect of gold, he made the journey to Western Australia, worked in Geraldton, married in Subiaco and lived for some time in Cue. Eventually, in 1902, he settled in Collie. Working initially as a miner, his luck turned when his wife came into an inheritance, enough for him to establish himself as a watchmaker and jeweller in the town. At George’s urging, Charlotte decided to start a new life for herself and her boys in Western Australia and in April 1911, accompanied by Frank, she had her first glimpse of her new country from the deck of the Omrah. Fred, who had been apprenticed to a mechanic and later worked in that capacity for Wolf and Son in Liverpool, joined them some two years later. Boarding in the Dobson’s home with his mother, Frank found work in the Water Department where it seems he formed a bond with Arthur Arney, the Department’s irrigation and drainage engineer. Frank was also keenly interested in the land and farming. Frederick in contrast was drawn to the sea and worked as a mariner in Fremantle.

War is Declared

Meanwhile storm clouds had been gathering over Europe for some years and

……. when the magic message appeared, (that Great Britain had declared war on Germany), the crowd broke out into rousing cheers, adding another for the King. The cheers quickly brought up great numbers of people from neighbouring streets, and soon the news was scattered, broadcast through the city. Everywhere it was received with enthusiasm, the people being glad that doubt had given place to certainty, even when that certainly meant grim war. It was felt that war had to come, and everyone was agreed that the sooner it came the quicker it would be over. Daily News August 5, 1914

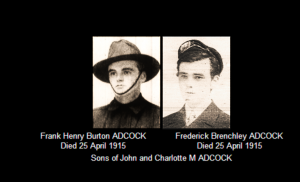

Frank Adcock (left) was amongst the first in the rush to join up, he was given Regimental #394 and appointed to the original D company of the 11th Battalion.

Frank Adcock (left) was amongst the first in the rush to join up, he was given Regimental #394 and appointed to the original D company of the 11th Battalion.

Frederick (right) made his decision a month later and with the 11th Battalion already full by the time he arrived at Blackboy Hill, he was assigned to 16th Battalion and given the Regimental # 7. He was only with them a short time before he managed to organise a transfer and join his brother in the 11th Battalion with a new Regimental #1044.

Both must have felt a sense of good fortune having the opportunity to fight for their Mother Land as part of the AIF rather than the British Army. An Australian private received six shillings a day, the highest private’s pay in any army in the war. The British soldier was paid by comparison, only a shilling a day. One can only imagine Charlotte’s thoughts as she stood again on the wharf at Fremantle on 31st October, 1914 and watched her boys leave Australia on the troopship Ascanius. As for Fred and Frank,

... with their homeland fading into the horizon behind them, the sea tranquil and the weather glorious, the men and boys settled in for a long voyage, to adventure, a war and destinations unknown.

In the Land of the Pharos

Twenty six days into the voyage, the men received the news that rather than going to England to train, they were headed for Egypt. For some, the news was greeted with delight, for others who had been born in Britain, there was disappointment. Many had enlisted expecting to be able to visit family in the mother country.

Twenty six days into the voyage, the men received the news that rather than going to England to train, they were headed for Egypt. For some, the news was greeted with delight, for others who had been born in Britain, there was disappointment. Many had enlisted expecting to be able to visit family in the mother country.

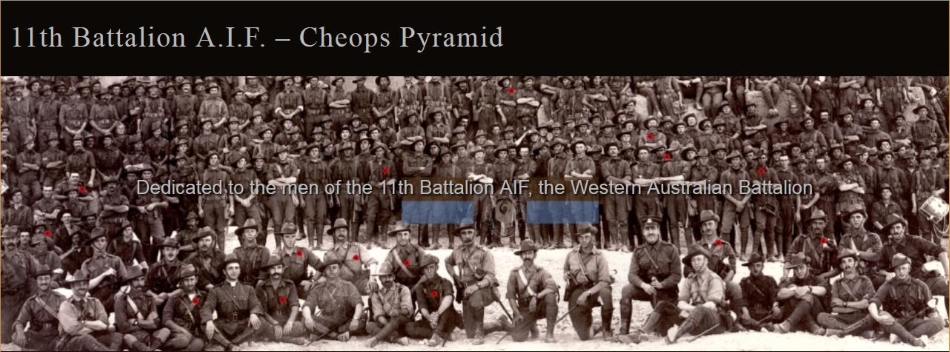

We know from the diaries and letters of members of the 11th, that the novelty of life in Egypt soon evaporated as they grappled with sickness, sandstorms, locusts, heat and monotony. Nevertheless, all appeared in good spirits when on 10th January 1915, 704 of the 1024 strong battalion marched to the Great Pyramid arranged themselves on one of its four sides and had their photo taken. Frank (ID#343) and Fred (ID#341) were seated side by side in what was possibly their last photo together.

The Landing at Ari Burnu

Many military historians have described in great detail, the experiences of the men of the 11th Battalion on the 25th April 1914 as well as the days leading up to it. Suffice it to say, when survivors mustered for roll call on the beach within days of the landing at Ari Burnu, neither Fred nor Frank could be accounted for. Fremantle City Archivist and Military Historian, Andrew Pittaway takes up the story in the following excerpt from his article Only a small proportion returned: the Adcock Brothers, 11th battalion AIF

"What had happened to them?

First reports that came back to Australia in June 1915 were that both boys had been wounded with nothing further being known. With no more news coming in, an anxious Charlotte Adcock began contacting the local Defence Authorities and the Red Cross. Towards the end of 1915 encouraging news began to appear from soldiers returning from stints in hospital that the Adcock brothers were okay though even these reports were conflicting.

No.983 Pte William Shields[i] stated that; “They were both in the original landing, and both survived it and were both alright about three weeks later, though one had been wounded in the hand and lost some of his fingers, and the other (the elder) had been shot through the lungs. The elder was in No.15 General Hospital at Alexandria” On returning to the 11th, Corporal Kirton[ii] of B Company told a member of the Adcock’s platoon that both the brothers had been in England with him at Manchester hospital. This brought some hope to Charlotte that her sons may still be well but a search of the hospitals in Alexandria and England could find no soldiers by that name.

Had Kirton and Shields mixed up the Adcocks with one of the other sets of brothers of B Company, several of whom had been in hospital in Egypt and England? Shields admitted that he did not know the brother’s first names so it’s possible that not knowing them well he confused them with others. Unfortunately Kirton could not later expand on what he said as he died early in 1916.

Increasing the mystery of what happened was that Charlotte received a postcard from Frank apparently dated 1st May 1915 and postmarked the 21st May 1915 which stated that; “Fred and I have been cruising about in an old whaler for the past month. We have had a glorious time. Occasionally we would take a walk over the hills” An unnamed wounded returned soldier stated that while on Lemnos the two brothers had run stores from the shore to the transports and this sounds like what Frank’s postcard refers to. Was this postcard held up in Egypt by the Postal Service or was it sent on and dated by a well-meaning soldier friend of the Adcocks. We may never know the real answer.

Despite much letter writing, Charlotte never found what had actually happened to her two sons and by the time a Court of Inquiry was held at Fletres in France in April 1916, there seemed to be no one in the battalion who could shed any further light. Both Frank and Frederick were therefore listed as Killed in Action on April 25th 1915.

Charlotte, by now living in the mining town of Collie Burn, WA, sadly accepted this official news and in June 1916 wrote to authorities for both her sons’ death certificates. However, Vera Deakin of the Red Cross continued to search for information for Charlotte and wrote to original members of B Company in the hope they could shed more light on their fate. In July 1916, Vera contacted No.493 Sgt Baxter Westbrook[iii] of the 11th. He stated that Frank and Fred Adcock along with other members of his platoon, No.412 Pte James Carrington[iv]; No.423 Pte Arthur Devenish[v] and No.444 Pte Ernest Hearle[vi] had landed with him but he had become separated from them and had seen nothing more of any of them since that time.

Did the Adcock brothers therefore die with the other men of their platoon, well in front of Quinn’s? However in August 1916, further news came in from No.416 Pte Percy Clark[x] who was recovering from wounds received in France. He stated that; “On April 25th on Anzac Beach I saw one of the Adcock Brothers being carried on to a hospital ship wounded. I cannot tell which one it was. I was running past the stretcher and called out to him. I was afterwards told that he had died. My informant was C Braidwood[xi] B Company 11th Battalion. Braidwood was also wounded at the same time and recovered and was sent out again. I hear he has again been wounded.

On the home front

Charlotte ADCOCK ca.1915

Whilst her boys remained missing and unaccounted for, Charlotte had other family issues to contend with.

Whilst her boys remained missing and unaccounted for, Charlotte had other family issues to contend with.

Her brother George who was deemed too old for active service joined the war effort as a munitions worker and was sent to England for the duration of the conflict. His daughter, Frances, came to live in Fremantle with her ‘Aunty Lot’, as Charlotte was called by the family, to ease the burden on George’s wife and it was during this time with great generosity, she organised and paid for her nephew, Richard Atkins to attend Guildford Grammar School.

Just as Charlotte received the verdict of the Court of Inquiry into the fate of her boys, George’s eldest son, fifteen year old James Fielder Atkins, who had suffered brain damage after falling out of a tree some four years earlier, died on the 26th April, 1916. It was one year and one day after the Anzac landing, the day on which it was determined that Charlotte’s two sons had been killed.

With her two boys now declared dead, their wills were executed in Perth with each leaving £215, most likely their army entitlement. Frank’s legacy went to Arthur Arney, perhaps as repayment of a loan, whilst Fred’s legacy went to his mother.

Eternal Rest

Andrew Pittaway tells us:

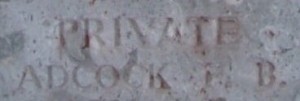

When the task came of reconstructing the Gallipoli War Cemeteries, members of the Imperial War Graves Commission made a search for battlefield burials and isolated graves were repositioned and bodies recovered. News eventually came through that Frank Adcock’s body had been recovered though records are scant on how and where he was found. He was then buried up at Baby 700 Cemetery in plot D.24, around other men who had fallen that first day of fighting. The men buried on either side of Frank; No.817 Maurice O’Donohue[xii] of the 11th Battalion and No.274 Leslie Clifford[xiii] of the 2nd Battalion had been found buried on or nearby Baby 700 and the same must have been true for Frank. As this ground was hotly fought over on day one and not occupied by the Australians after April 25th it’s a strong possibility that Frank was buried by the Turks after they had pushed the Anzacs back off Baby 700 for the final time. 493 men are buried in this cemetery but only 43 are known by name. Charlotte chose the following epitaph for Frank’s headstone;“My Truth is a Sword”

Private ADCOCK F.H.B. - Baby 700 Cemetery.

Image courtesy Andrew Pittaway

With Frank identified and buried at Baby 700 Cemetery this would mean that it was Frederick Adcock that Percy Clark saw being sent on a stretcher to the transport ship If Fred had died of wounds aboard one of the ships he would have been buried at sea and with all the confusion over the large numbers of wounded, the authorities on board did not seem to record the names of the large numbers of wounded who had died.

Thus Frederick is commemorated on the Lone Pine Memorial.

Private ADCOCK F.B. - Lone Pine Memorial.

Image courtesy Andrew Pittaway

It’s not surprising that in 1920, having been allocated a pension of £1 a week as compensation for the loss of two sons, Charlotte returned to England. Her great niece, Joy remembers her mother, Frances receiving regular parcels from Charlotte with the return address of Symonds Yat, Herefordshire. It was there, in early 1947, having lived through yet another World War, she died aged 87 – Peace at last. Note : In 2008, several WWI names were submitted to the Fremantle Council for inclusion in the database of new street names. Of these, Adcock was the first to be utilised.

Researched and written by Julie Martin - Quotes from an article by Andrew Pittaway, used with permission

Soldiers mentioned

[i] Pte William Shields – Sleeper Hewer of East Kirrup – Returned to Australia but re-enlisted in 1917 and returned to 11th Bn with Reg. No.8042. Red Cross statements.

[ii] QMS Alec Kirton – Bank Clerk of East Fremantle – Died of Injuries Egypt 18th February 1916. Red Cross

[iii] Sgt Baxter Westbrook – Labourer of Fremantle. He was badly wounded in the 11th’s last fight on September 18th 1918 and had his arm amputated. He died in 1925. Red Cross Statements

[iv] Pte James Carrington – Blacksmith of South Fremantle KIA 25th April 1915

[v] Pte Arthur Devenish - Warehouseman of Victoria Park – KIA 25th April 1915

[vi] Pte Ernest Hearle – French Polisher of Fremantle – KIA 25th April 1915

[vii] Sgt Jim Durward – Labourer of South Fremantle – Returned to Australia 1920. Red Cross Statements

[viii] Sgt John Chamberlain – Lumper of Fremantle – KIA 25th April 1915

[ix] Lt Duncan Sharp – Fireman of Fremantle – KIA 10th August 1918. Red Cross Statements [x] Pte Percy Clark – Fireman of Collie – KIA 30th October 1917. Red Cross Statements

[xi] Pte Charles Braidwood – Tailor of Fremantle – Returned to Australia October 1918 – Died October 1970

[xii] No.817 Pte Martin O’Donohue – Teacher of Northam and Kalgoorlie – KIA 25th April 1915

[xiii] No.274 Leslie Clifford – Grazier of Bredbo NSW – Is listed officially as KIA 2nd May 1915 but he had been posted missing since April 25th. His brother Conyers Clifford was killed in Egypt with the 7th Light Horse in 1916.

_________________________

Sources

Caulfield, Michael – The unknown Anzacs

Hurst, James – Game to the last.

Pittaway, Andrew - Only a small proportion returned: the Adcock Brothers, 11th battalion AIF in Digger: Magazine of the Friends and Families of the First AIF 2010, June. No 31

NAA: B2455, ADCOCK Frederick Brenchley- NAA: B2455, ADCOCK Frank Henry Burton Australian Red Cross Society – Wounded and missing Enquiry Bureau files, 1914-18 War 1DRL/0428 – 394- Private Frank Henry Burton ADCOCK Australian Red Cross Society – Wounded and missing Enquiry Bureau files, 1914-18 War 1DRL/0428 – 1044- Private Frederick Brenchley ADCOCK

Census Returns of England & Wales. RG12 1891, RG13 1901 England & Wales.

National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations) 1858-1966 London.

Metropolitan Archives. St James, Hatcham Register of Marriages P75/JS1.

Item 062 Adcock Boys and Gallipoli Landing Images from The Australian War Memorial online archives